Meet the woman who contributed to the discovery of DNA's double helix, but whose contributions to modern science have largely been forgotten.

The immediate post-WWII annual photographs of Cavendish Staff and Research Students are remarkable for the small numbers of women present, despite their huge contributions to the war effort. One of the few women present in the 1947 group photo (Fig.1) is June Broomhead, whom we celebrate the centenary of her birth this year. She died last year in Ottawa, Canada at the age of 99.

As recounted in the obituary published in IUCr Newsletter, (Lindsey et al 2022), June was born in a small Yorkshire village. During her school years, she was inspired by the story of Rutherford’s contributions to basic physics and in due course went up to Newnham College, Cambridge on a full scholarship, the first from her school to attend the University.

Once at Cambridge, she soon became aware of Lawrence Bragg and the crystallographic work at the Cavendish. As she wrote later:

‘When I first went up to Cambridge, I hadn't even heard of [X-ray crystallography], but by a fortunate fluke, chose to study just those sciences which are most essential … physics, chemistry, mineralogy, and mathematics.’

Fig 1. The Annual Cavendish Staff-Research Student photograph for 1947. June Broomhead is seated on the far right next to Brian Pippard. Lawrence Bragg is in the centre of the front row and on his left Will Taylor. Bill Cochran is seated cross-legged fourth from the left in the front row and George Lindsey, June’s future husband, third from the right in the back row. Max Perutz is sixth from the left in the third row from the top.

She was awarded a research studentship on graduation and in 1946 returned to the Cavendish to pursue a PhD under W.H. (Will) Taylor. Once there, June developed a friendship with the distinguished crystallographer Bill Cochran, to whom she attributed much of her future success.

In August 1948, she submitted her paper ‘The structure of pyrimidines and purines. II. A determination of the structure of adenine hydrochloride by X-ray methods’ to the new journal Acta Crystallographica (Broomhead, 1948). In addition to measuring the physical dimensions of adenine, she stated:

‘Hydrogen bonds linking a purine molecule to chlorine atoms and to water molecules, and short van der Waals contacts with other purine molecules lie approximately in the plane of the molecule’.

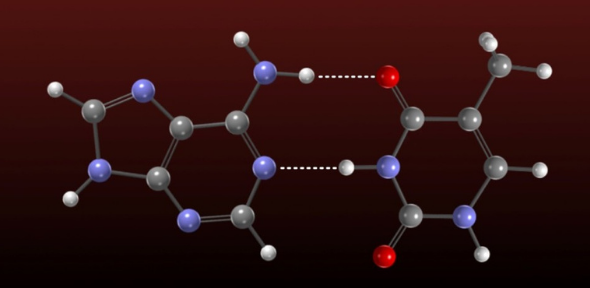

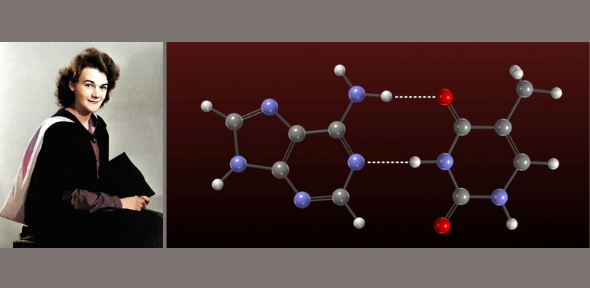

This observation was the key to James Watson’s discovery six years later of the base pairing shown in Fig. 2.

Next, June determined the structure of thyamine (Broomhead, 1951). With these precise measurements of the dimensions of molecules, the two nucleic acid strands could thus be evenly joined, adenines linked with thymines and cytosines with guanines, while satisfying Erwin Chargaff's earlier observation that DNA comprised equal quantities of adenines and thymines as well as of cytosines and guanines (Chargaff 1950).

Fig 2. Illustrating the structures of adenine (left) and thymine (right) as well as the hydrogen bonding between them. Carbon atoms are gray, nitrogen atoms blue, oxygen atoms red and hydrogen atoms white (Lindsey et al. 2022).

Following her successful defense of her doctorate ‘An X-ray investigation of certain sulphonates and purines’ in 1950, June moved to Oxford to work with Dorothy Hodgkin on vitamin B12 (Brink et al., 1954). In 1951, she moved to Ottawa with her Canadian husband, George Lindsey, who had also studied for a PhD in physics at Cambridge. She took up a postdoctoral position at the National Research Council of Canada and identified the crystal structure of codeine (Lindsey & Barnes, 1955). When she moved with her husband to Montréal and following the birth of their two children, she retired after almost a decade of very impressive research achievements.

There is no mention of her contribution in the famous Watson and Crick Nature letter of 1953, but her name is present in the longer paper published in Proc. Roy. Soc. in the following year.

There it is stated:

‘The crystal structures of both adenine and guanine have been studied by Broomhead (1948, 1951) … More recently Broomhead’s data on adenine have been refined by Cochran (1951) and the atomic parameters of this compound are now accurate to within 0.02 Å.’ (Watson and Crick 1954)

In 1952, Max Perutz and his colleagues were struggling with the problem of determining the very complex structure of the huge haemoglobin molecule. In a touching letter to June, Nobel laureate Sir Lawrence Bragg wrote:

‘We badly need your hands to tackle knotty crystallographic problems, both experimental and theoretical. I wish all these things had come up while you were still with us; they would have been just in your line.’

Watson and Crick could not have made their dramatic discovery of matching up the base pairs without June’s expert crystallographic studies. It is clear that June was a brilliant scientist who played a crucial role in one of the greatest discoveries of the 20th century and it is about time this is finally publicly recognised.

This article originally appeared in CavMag issue 27 (Spring 2022)