2025 Cavendish Annual Thesis Prize Winners

17 January 2025

Three exceptional PhD students have been awarded a Cavendish Annual thesis prize for their achievements in computational, experimental, and theoretical physics research. Camilla Tacconis, Emmanuel Gottlob and Pratyush Ghosh have been selected by a panel of judges for their outstanding contributions in their fields.

The winners received their prizes and presented their award-winning work as part of the graduate student conference on Wednesday 15 January. Each prize comes with a cheque of 500 pounds.

Their projects cover a wide range of topics, looking into some of the most pressing challenges of the 21st century. From developing materials for next-generation rechargeable batteries to studying the quantum ‘dance’ of atoms and electrons and the fundamental challenges of optical quasicrystals, our prize winners tell us all about their research below.

Emmanuel Gottlob, winner of the Abdus Samal Prize

‘Hubbard Models for Quasicrystalline Potentials’, Phys. Rev. B, April 2023. DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevB.107.144202

Most materials around us, from table salt to metals, are made of atoms arranged in regular, repeating patterns – like the tiles on a bathroom floor. But in the 1980s, scientists discovered quasicrystals, which break this rule: their atoms form ordered patterns that never repeat exactly. These materials might exhibit extraordinary quantum behaviors – one of the most intriguing is called many-body localisation, where the material can get “stuck” in a quantum state and never reach equilibrium. This would be like a drop of milk in coffee that never mixes, defying our usual understanding of how things naturally settle into thermal equilibrium. While natural quasicrystals are extremely rare – found only for instance in meteorites and the remains of the first atomic bomb test – physicists can now create artificial versions called optical quasicrystals by shining laser beams onto ultra-cold atomic clouds. These optical quasicrystals serve as “quantum simulators,” allowing us to study the strange properties of these materials in a clean and controlled way.

In the highlighted research paper, I tackled fundamental challenges in studying optical quasicrystals. To understand how particles move and interact in quantum systems, physicists use simplified models called Hubbard models. These models describe particles hopping between specific localised orbitals. However, constructing these orbitals traditionally only worked for regular, repeating crystals. I developed new methods to extend these tools to optical quasicrystals, creating computational techniques that allow us to model these systems at unprecedented scales – four times larger than was previously possible. The new large-scale model lets us see fine details in the behavior of optical quasicrystals that were invisible before. Additionally, I discovered a new mathematical way to describe infinite-sized quasicrystals. Just as periodic crystals can be understood through their “Brillouin zones,” I found that quasicrystals can be understood their “configuration space” – an alternative representation where lattice sites are re-arranged according to their shapes and local surrounding. This second advance enables the first rigorous understanding of optical quasicrystals’ infinite-size physics emerging from their fractal structure, and paves the way for exploring the existence of the many-body localised phase in these systems.

Undertaking my PhD at Cambridge was truly special. The Cavendish laboratory offered an excellent environment, with a diverse array of research subjects and world class seminar speakers. Perhaps even more important to my academic success was the college system. Colleges are amazing places that allow you to build meaningful friendships and practice a super diverse range of activities with people studying all subjects. My college (Trinity Hall) provided me with an invaluable group of supportive friends, which made my years in Cambridge unforgettable!

The Abdus Salam Prize for Postgraduate Student Research has been donated to the Department to be presented to a Research Student at the Cavendish.

Illustration: looping video representing the optical quasicrystal studied by Emmanuel.

Camilla Tacconis, winner of the Cavendish PhD Prize

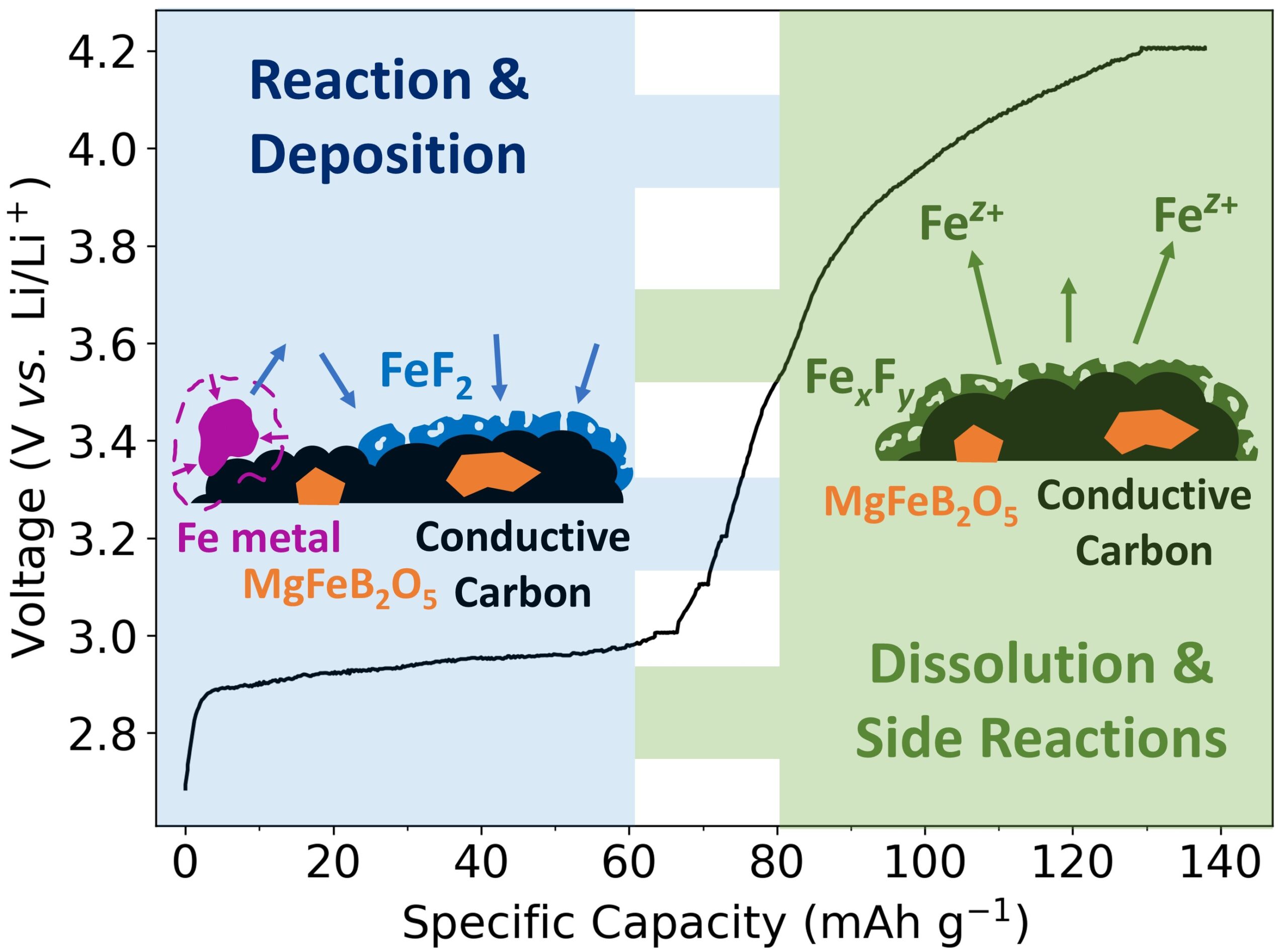

‘Role of Fe Impurity Reactions in the Electrochemical Properties of MgFeB2O5’, Chemistry of Materials, 2025. DOI: 10.1021/acs.chemmater.4c02855

Camilla Tacconis (Jesus College) is a final year PhD in the ‘Functional Energy Materials’ Dutton Group. Her work focuses on the use of solid-state physics combined with electrochemistry, to develop materials for next-generation rechargeable batteries. She has spent her PhD synthesising novel materials from the class of magnesium borate polyanions and studying their viability as high voltage cathodes for rechargeable Mg-ion batteries. This interdisciplinary field involves inter-departmental work, with strong ties to Prof. Dame Grey’s group at the Yusuf Hamied Department of Chemistry.

“This research project was a lesson in perseverance, it was really hard to stick to a project that from the start delivered many disappointments and dead ends. My supervisors on the project, Prof Sian Dutton, Prof Dame Clare Grey and Dr Sunita Dey, were a huge support in guiding and motivating me to keep asking questions until I reached the answers I was looking for. The perseverance paid off, and thanks to a valuable international collaboration with Dr Moulay T. Sougrati at the University of Montpellier, supported by the STFC Batteries Network ‘Early Career Researcher Award’, I was able to understand my battery performance and identify a novel irreversible reaction mechanism.”

Pratyush Ghosh (St. John’s), winner of the Cavendish PhD Prize

Decoupling excitons from high-frequency vibrations in organic molecules’, Nature, 2024. DOE: 10.1038/s41586-024-07246-x

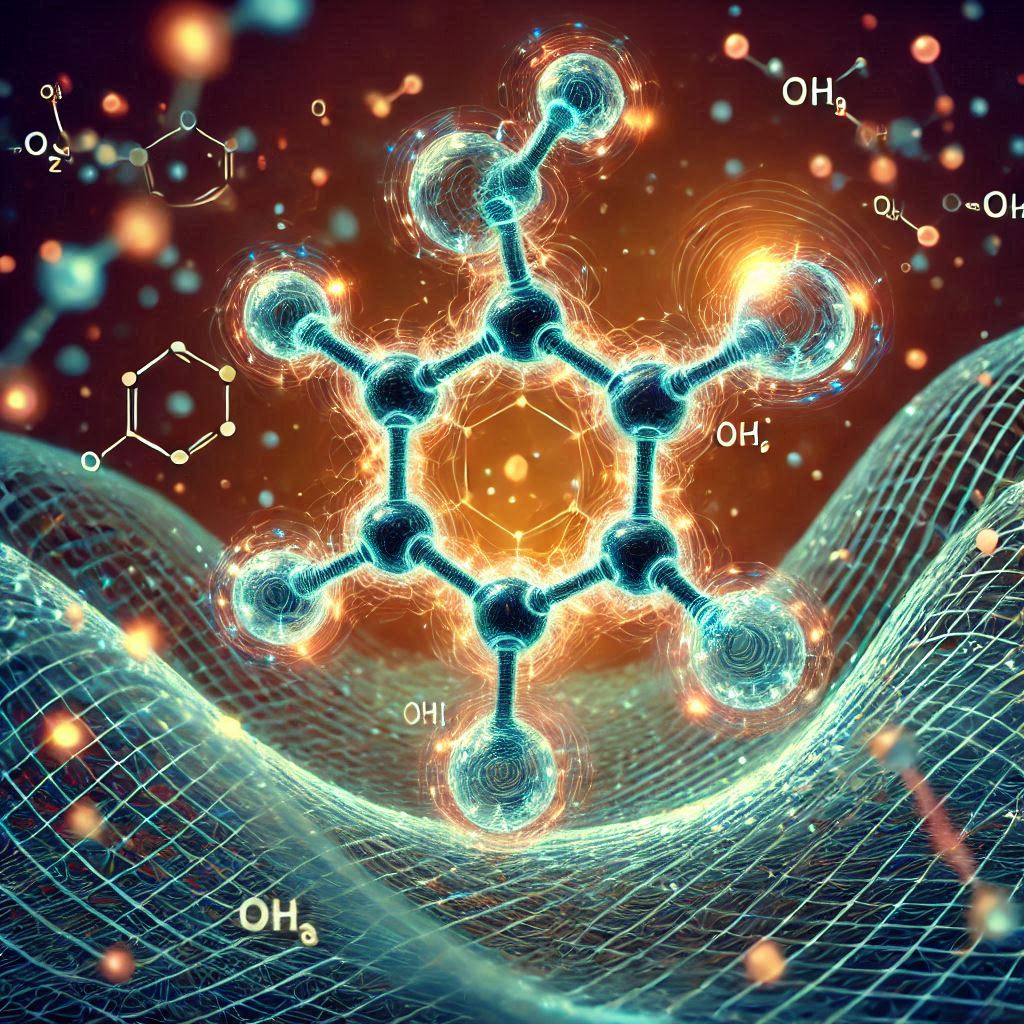

We have discovered how to halt the quantum “dance” of atoms and electrons in carbon-based organic molecules, paving the way for improved light-emitting molecules used in displays and biomedical imaging. This research introduces molecular design principles that decouple electrons from atomic vibrations, enhancing molecule performance significantly.

Electrons in organic molecules are often coupled to molecular vibrations, the periodic motion of atoms resembling tiny springs. This coupling leads to energy loss, limiting the efficiency of organic materials in applications like OLEDs, infrared sensors, and fluorescent biomarkers for disease detection. By using advanced laser-based spectroscopic techniques, the team has devised design rules that minimize these detrimental interactions, essentially “shutting down” the molecular dance.

“All organic molecules, such as those in living cells or phone screens, are composed of carbon atoms linked by chemical bonds that vibrate like springs,” explained PhD student Pratyush Ghosh, the study’s first author. “These vibrations typically hinder electron performance, but by carefully controlling the molecule’s geometry and electronic structure, we can mitigate these effects.”

To demonstrate, the researchers designed near-infrared emitting molecules (680–800 nm) with energy losses from vibrations reduced by over 100 times compared to previous designs. These efficient molecules show promise for enhanced displays, superior imaging agents, and innovative disease-detection tools.

This work sets the stage for cutting-edge advancements across multiple industries.

Conducting my PhD research at Rao Group has been an extraordinary journey. The collaborative environment, access to cutting-edge facilities, and the opportunity to engage with brilliant researchers have been pivotal in shaping my scientific outlook and contributions.

Image: Artist’s illustration of an organic molecules light emission property modulated by quantum dance of the atoms.

Lead image:

Left: Camilla Tacconis holding one of her batteries, in front of the glovebox.

Right: Artist’s illustration of an organic molecules light emission property modulated by quantum dance of the atoms. Credit : Pratyush Ghosh